During the early stages of erosion, the eroded areas are very sensitive to heat and cold, acid foods, and toothbrushing, but sensitivity may decrease when secondary dentin is formed.

DENTAL CARIES

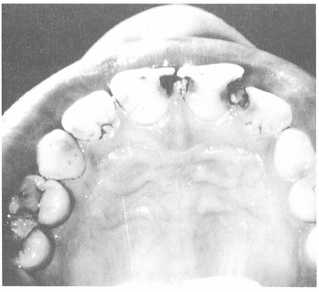

Man has suffered the effects of dental caries for centuries, and much study and research have been devoted to their causes and prevention. The disease is caused by a microbial process that starts on the surface of the teeth and leads to the breaking down of the enamel, dentin, and cementum, in some cases causing pulp exposure. This pathologic break that is produced on or in the tooth surface is called acarious lesion (fig. 5-4) or commonly called a cavity. The process that destroys the hard surfaces of the tooth is called decay.

Contributing Factors

The cause of tooth decay has been linked to a group of bacteria called streptococci and other acid producing bacteria that are in the oral cavity. Decalcification of the enamel, the first step in the decay process, is caused by:

Bacterial plaque adhering to the smooth surfaces of the teeth

Acid, produced by bacteria in food debris, being trapped in pits and fissures

Decay Process

Dental caries usually appear first as a chalky white spot on the enamel, which indicates the decalcification process. If proper oral hygiene is not maintained, the lesion may become stained and take on a dark appearance. In pit and fissure caries, the area of decalcification at the surface is normally small, and the white spot is less noticeable than in smooth surface caries. In either type of caries, the surface becomes roughened, as can be noted by passing a dental explorer point over it. If the tooth surface has an area that has not progressed past the decalcification stage, this type of carious lesion is called incipient. As the decay spreads in the enamel, it may stop. If this occurs, the process is called an arrested carious lesion (fig. 5-5). These areas in which dental caries have been arrested are dark and, in some instances, hollowed out. A dental explorer passed over or in these areas will feel hard to the touch. If the areas still has active decay, the explorer may “sink in” the soft decay.

Dental caries can progress further into the dentin of the tooth, and spread out laterally widely undermining the enamel and dentin. If this occurs, often there may be no visible changes until extensive destruction has taken place. The condition of the caries if not arrested or restored with operative dentistry (filling) will spread through the dentin into the pulp of the tooth, thus requiring endodontic treatment (root canal).

Figure 5-4. - Carious lesions.

Continue Reading