Blood Coagulation

To protect the body from excessive blood loss, blood has its own power to coagulate, or clot. If blood constituents and linings of vessels are normal, circulating blood will not clot. Once blood escapes from its vessels, however, a chemical reaction begins that causes it to become solid. The clot formed is at first fluid but soon becomes thick and then sets into a soft jelly that quickly becomes firm enough to act as a plug. This plug is the result of a swift, sure mechanism that changes one of the soluble blood proteins, fibrinogen, into an insoluble protein, fibrin, whenever injury occurs.

Other necessary elements for blood clotting are calcium salts, a substance called prothrombin, which is formed in the liver, blood platelets, and various factors necessary for the completion of the successive steps in the coagulation process. Once the fibrin plug is formed, it quickly enmeshes red and white blood cells and draws them tightly together. Blood serum, a yellowish clear liquid, is squeezed out of the clot as the mass shrinks. Formation of the clot closes the wound, preventing blood loss. A clot also serves as a network for the growth of new tissues in the process of healing. Normal clotting time is 3 to 5 minutes, but if any of the substances necessary for clotting are absent, severe bleeding will occur.

HEMOPHILIA is an inherited disease characterized by delayed clotting of the blood and consequent difficulty in controlling hemorrhage. Hemophiliacs may bleed to death as a result of even a trivial wound.

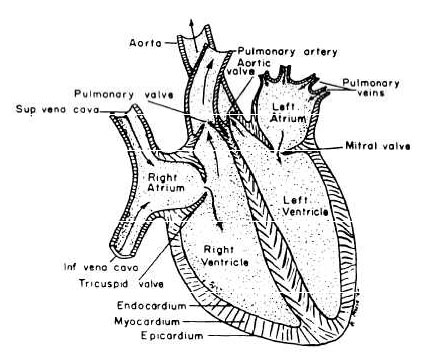

Figure 3-30.—Diagram of the heart.

THE HEART

The heart is a hollow, muscular organ, somewhat larger than the closed fist, located anteriorly in the chest and to the left of the midline. It is shaped like a cone, its base directed upward and to the right, the apex down and to the left. Lying obliquely in the chest, much of the base of the heart is immediately posterior to the sternum.

The heart is enclosed in a membranous sac, the PERICARDIUM. The smooth surfaces of the heart and pericardium are lubricated by a serous secretion, the pericardial fluid. The inner surface of the heart is lined with a delicate serous membrane, the ENDOCARDIUM, similar to and continuous with that of the inner lining of blood vessels.

The interior of the heart (fig. 3-30) is divided into two parts by a wall called the INTERVENTRICULAR SEPTUM. In each half is an